School shootings began about two and a half decades ago and have oddly become more common than anticipated. They are similar to mass shootings or potentially falling under the category of them. A school shooting would best be defined as an event taking place at an educational institution in which someone, typically a student from the particular school being targeted, invades the school with a firearm and harms individuals. The student is usually enrolled in the school at the time of the shooting or, in some cases, had attended it in the past. The results are predominantly very disturbing and unfortunate, leaving a whole community, in fact, the entire nation in which it occurred, shaken and heartbroken. Moreover, since the first major and noted shootings in the late 1990’s, they have begun to trickle in year after year, seemingly peaking the interest of so-called “fans” (future school shooters). As a result, we are left with one question and that is, why? Of course, no claims may be confirmed, and no single factor could be named the issue, but years of observation and research reveals morality, past experiences, video games, thresholds, and characteristics of schools to be among the most prominent and likely motivations for school shooters.

Morality and possession of favorable values are a large part of our society. It is also a form of regulation for individuals and for society as a whole. When such a thing is absent, so is the will to be cautious as well as empathetic. Values can derive from several different arenas such as upbringing, experiences, religion, or other environmental influences. In the article “Thresholds of Violence”, the author, Malcom Gladwell, who has been a writer for The New Yorker since 1996, introduces a strange but interesting scenario about a potential school shooter named John Ladue. He was a 17-year-old boy who a woman called the cops on based on suspicion. Three cops entered his apartment unit and discovered materials scattered and appearing to be for the making of a bomb. Ladue agreed that they were just that, and the cops took him in for questioning. During the interview, Ladue disclosed his plans to bomb his school and ultimately take as many lives as he could before taking his own. The resulting police report expressed his father’s concerns and attempts to make sense of how his son could have had such plans without conveying the slightest hint through his actions or personality/demeanor. In the police report and according to Ladue’s father, a portion provided that “’[Ladue] had stayed with his brother for a couple of months at the beginning of last summer [and…] had returned proclaiming to be an atheist, stating that he no longer believed in religion’” (Gladwell). Here, it is understood that Ladue’s plans began after being away with his brother and becoming an atheist. This evidence shows that Ladue may have potentially possessed some set of values prior to his visit with his brother, as his unexpected plans for the attack were formulated afterward. In addition, he made a transition and decided against religion. As a result, Ladue may have lost the only regulatory figure he had in his life. In other words, Ladue and his newly-found closure to his religious past may have been an explanation to his also new lack of morals. Of course, no claim is being made here that all atheists lack morality or are more likely to engage in unethical acts or violence. He just must not have had any other/additional self-regulatory facets within himself to help him stabilize his actions. Violence has most definitely been acted on in the name of religion, which goes to show that religious beliefs do not have an association with violence or a lack thereof. Ladue’s situation is different; looking into the order of events prior to his violent plans provides that his lack of morals most likely were a product of his decision to step away from them, which he did just as he departed from his religion. Just as federal and state laws, police officers, the fear of prison time, authoritarian parenting, and other possible factors have similar effects on people, religion can fall into the same regulatory category and, therefore be one of the plausible explanations to why people do or do not engage in certain activities.

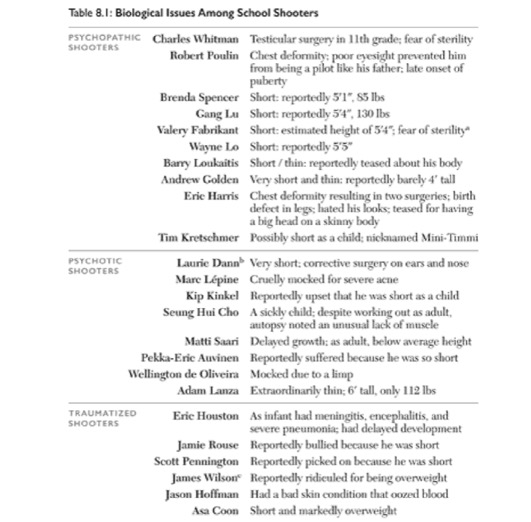

Furthermore, past life experiences sometimes also play a vital role in the motivation to commit school shootings and intentional violence. This may include a wide range of past life or traumatic events such as parental divorce/separation, bullying, assault or abuse, and exposure to first-hand violence. The majority of past school shooters had separated parents. Adam Lanza, Karl Pierson, the Tsarnaev brothers, Mitchell Johnson, and Ronald E. McNair are just a few examples (Langman, “School” 140). In addition to separated parents, trauma and harmful childhood exposure comes into play. Almost all of previous school shooters have experienced some form of trauma as a child and/or into their teenage years. Peter Langman, author of Why Kids Kill: Inside the Minds of School Shooters and School Shooters: Understanding High School, College, and Ault Perpetrators as well as clinical psychologist and school shooters expert, described a single trauma to have a “profound impact on a child; the traumatized shooters each endured multiple traumas” (Langman, “Why” 111). Langman illustrates the severity of trauma and backs the idea up with the fact that shooters typically have endured past traumatic experiences that caused them to act as they did when committing the heinous crimes that they had. These traumatic experiences may include exposure to parents engaging in drug abuse or violence towards each other. Endurance of bullying in school or elsewhere as a child is also detrimental. Experiences as such may result in low self-esteem or feed on existing insecurity. In the book School Shooters: Understanding High School, College, and Adult Perpetrators, also by Langman, a chart on page 159 is provided to elucidate truth to this claim through a list of school shooters with their insecurities or reality regarding their appearance that they struggled with. It is very interesting to see as it becomes evident down the list that these physical insecurities are a largely common factor among the shooters.

Figure 1 (Langman “School” 159)

It was shared among them the physical trait of being shorter or smaller than average. A handful was also overweight, some too thin, and others had late puberty. Either way, it seemed excessively bothersome to these children that they lacked an average physical appearance and/or the ability to fit in (as a result). It is very important to note how similar this list portrays these killers to be in comparison with one another as it could bring the search for the motives behind school shooters on to simpler terms.

Videogames have always been a go-to cause for school shootings. It being one of the most well-known and largest motivations have resulted in controversy surrounding it and whether it truly can result in such incidents as mass shootings. With enough evidence pointing to videogames as a potential source, it can safely be named one of the many possible factors. Popular videogames such as Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty contain firearms, graphic bloodshed, and the ability to murder freely. A similar videogame called Doom came out in the early 1990’s (Sternheimer). Its contents, similar to the mentioned games, contained graphic violence and provide warnings as well as an age minimum in order to play it, though hardly any gamers pay attention to the restriction. In the article “Video Games Kill”, author Karen Sternheimer, who is a sociologist at the University of Southern California, provides that the game became prey to critics. She also supplies the details behind the aftermath of the videogame’s release and its apparent connection with school shootings:

“In the years after its release, Doom helped video gaming grow into a multibillion dollar industry, surpassing Hollywood box-office revenues and further fanning public anxieties. Then came the school shootings in Paducah, Kentucky; Springfield, Oregon; and Littleton, Colorado. In all three cases, press accounts emphasized that the shooters loved Doom, making it appear that the critics’ predictions about video games were coming true.”

As mentioned, the game had apparently triggered a flurry of school shootings in the few years following its release. This kind of information points straight to the video game as a potential pusher. In addition to this, Sternheimer declared that the shooters all played the game, therefore, bestowing that the videogame could be a direct cause of the school shootings. In the article, “Thresholds of Violence”, Gladwell provided that Evan Ramsey, one of the many school shooters of the 90’s, may have also played the game. Gladwell indicated that “…Ramsey’s father thought his son was under the influence of the video game Doom” (Gladwell). This type of news leads researchers to believe, without a doubt, that videogames have a substantial amount of influence on children and young adults in the real world with the capacity of leading them to commit crimes as heinous as school shootings.

In addition to the many possibilities, one that is not among the commonly discussed would be the existence and unconscious utilization of thresholds (Gladwell). When putting thresholds hand in hand with school shootings, what is put together is that it becomes easier for someone to commit a school shooting once they have seen it a certain amount of times. What people look for and the number of reoccurrences that finally grants a person with enough comfort to commit the same crime varies vastly among individuals. Gladwell advises through his article to always observe a group rather than merely an individual’s motives to get the most accurate understanding. The way the threshold theory is illustrated by the author of the article is simple, yet complex. He defines thresholds as “the number of people who need to be doing some activity before [others] agree to join them” (Gladwell). He also demonstrates a model proposed by Granovetter, a researching sociologist and psychologist, as it illustrates the process in which thresholds extend to. The model is interpreted using the example of riots and how they form as well as evolve into what they are commonly known as. Gladwell wrote that “riots were started by people with a threshold of zero—instigators willing to throw a rock through a window at the slightest provocation. Then comes the person who will throw a rock if someone else goes first. He has a threshold of one” (Gladwell). He goes on to describe the following individuals. The next person would have a threshold of two, meaning they must witness the act of a rock being thrown twice until they decide it is okay. This process is ongoing and explains the fluctuating and divergent threshold numbers among people. Relating and applying this model back to school shooters, it is understood that each potential school shooter possibly has a threshold and depending on their number, they will act in accordance to it. For example, if Ladue’s threshold was three, he must have witnessed three prior school shootings, then decided it was time for him to act. The reasons for this range from the size of the consequences each shooter suffered to how “normal” it may come off for Ladue to act after a certain number of individuals have already acted in the same way.

Moreover, Gladwell also brings to the table a summarized thesis demonstrating that the ultimate problem found in all of this is apart from what most people may assume it to be. He claims that “the problem is not that there is an endless supply of deeply disturbed young men who are willing to contemplate horrific acts. It is worse. It is that young men no longer need to be deeply disturbed to contemplate horrific acts” (Gladwell). This is very important to consider and comprehend because the abundance of evidence only points to the fact that school shooters may just be copying each other rather than having some sort of psychological or trauma related issue to explain their actions. Thresholds are a largely possible and likely explanation among many others to school shooters and why they are so comfortable with committing such horrid acts of violence.

The characteristics of schools have become a newly found and salient element in the phenomena of school shootings. A study conducted by Roberto Flores de Apodaca and a group of four other researching sociologists explored the realms of schools in which school shootings occurred. What they had discovered displayed characteristics of schools such as size and others to be determiners of the likelihood of shootings. The researchers pointed out that “the size of a school’s enrollment, urban or suburban locale, public funding, and predominantly non-white enrollment were positively associated with fatal shootings” (de Apodaca, et al.). They have established through common findings that schools with a specific type of setting increases the possibility of school shootings. They have also unveiled that teachers and students who contribute to a segregated or isolation provoking atmosphere can also have the same results/effects. The study found that “…characteristics of schools that allow feelings of anonymity or alienation among students may help create environmental conditions associated with fatal school shootings” (de Apodaca, et al.). Supporting these findings, an article presented by the New York Times discussed violence and gun control as well alienation in correlation to the size of a community or area. The article was able to establish that “social isolation and alienation can be experienced more intensely in smaller communities” (Debate Over Guns). In summary, in addition to the size or characteristics of a school, the same characteristics of a “community or area” may also be just as relevant. Concluding from these findings, it is presented that the type of environment existing at a school and in an area is very important to ensure comfort and a family- like setting for students and all people. In schools, teachers as well as students and staff have a role in the conveyance of such an environment. The opposite results in bullying, feelings of loneliness or isolation on school grounds, and hatred for peers or teachers which can then lead students to want to harm their classmates or teachers.

School shootings, being the immensely controversial, confusing, unfortunate, and disturbing events that they are, may never truly be understood. There is an excessive number of possible factors that could explain them and even when it is thought to be fully explained, there are too many possibilities and too many areas in an individual’s life that could somehow lead them to commit a school shooting. From past traumatic life experiences to thresholds to characteristics of schools having an effect on a shooter’s decision, there will always be multiple theories, but never one, true, identified and proven one behind the ultimate question of, why?

Rock Valley College-ENG 103-D250-Dr. Courtney

8 May 2019

Essay for freshman college English course

Bibliography

de Apodaca, Roberto Flores, et al. “Characteristics of Schools in Which Fatal Shootings Occur.” Psychological Reports, vol. 110, no. 2, Apr. 2012, pp. 363–377, doi:10.2466/13.16.PR0.110.2.363-377.

“The Debate Over Guns, Violence and the Will to Act.” New York Times, vol. 162, no. 56001, 30 Dec. 2012, p. 8. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=84530527&site=ehost-live.

Gladwell, Malcolm. “How School Shootings Spread.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 16 Nov. 2018, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/10/19/thresholds-of-violence.

Langman, Peter. School Shooters: Understanding High School, College, and Adult Perpetrators. Google Books, 2015, books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MfQ1BgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=schoolshooters&ots=Nor6UT5TRb&sig=N_sTfVAlDgikdeFnEYiTzP7PvaE#v=onepage&q =school shooters&f=false.

Langman, Peter. Why Kids Kill: Inside the Minds of School Shooters. Google Books, Macmillan, 3 Aug. 2010, books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UUTtO5P6DncC&oi=fnd&pg=PT7&dq=minds if mass shooters&ots=pfhWObAqts&sig=50Wc8iD- R5GlQC5mn3SyGQIlLnw#v=onepage&q=minds if mass shooters&f=false.

Sternheimer, Karen. “Do Video Games Kill?” Contexts, vol. 6, no. 1, 2007, pp. 13–17. Google, Scholar, doi:10.1525/ctx.2007.6.1.13.