The Punitive Justice Model: Recidivism, Mass Incarceration, and Reintegration

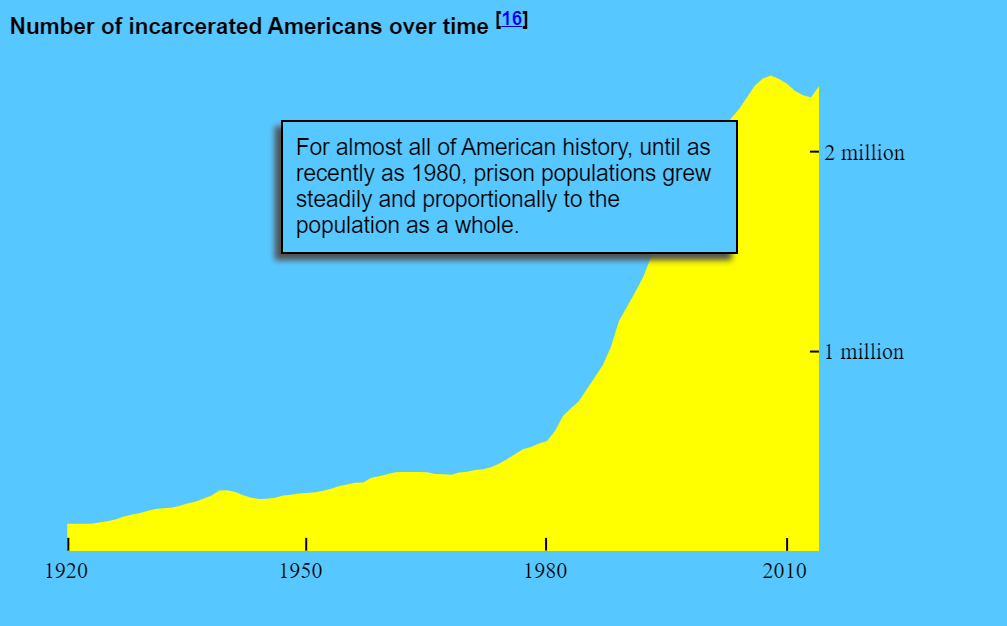

Rates at which individuals are incarcerated and reconvicted in the United States have exponentially increased since the 1980s, as there are more people imprisoned now than ever before (Nally et al. 2012; Jouet 2019).

The era of mass incarceration and penal policy as the norm emerged about four decades ago, and it became less common thereafter to question habitual legal procedure. After all, U.S. prisons and jails currently hold approximately 2.3 million inmates and coming, which is about a quarter of the global prison population (Link and Williams 2017).

The legal system plays a salient role in the dispersion of inmates in the disproportionate prison population, as it is best bigoted and targeting minorities, particularly Blacks and others of color. Prison conditions, in large part, are what can safely be blamed for high recidivism rates at the least. In 2008, there were 409,300 prisoners released, and there were 2.2 million arrests among just this group within the next 10 years (Antenangeli and Durose 2021). This would make the average prisoner commit five to six additional times following their release, which is clear-cut evidence that American penitentiaries are failing, namely at their purpose, and they amplify recidivism.

And to no surprise, most U.S. prisons give minimal attention to the well-being and improvement of inmates, largely because their fundamental goal is to deprive and punish. This would explain why inmates often have no windows in their cells, stone-hard beds, and little to no access to libraries or an education. Although the system is grounded in punishment and retribution, the question remains of what the desired outcome is for inmates. Is it for them to get better or worse?

Moreover, about 60% of the prison population is Black or Hispanic, despite them making up only 28% of the U.S. population (Sakala 2014). Throughout history, Blacks have been scapegoated and fixed on politically, from the Jim Crow era to the war on drugs.

Prison conditions and the dilemma of unprecedented incarceration has become historically significant, and since this point of peak-reaching, the Supreme Court had challenges pass through its walls. A California “three-strike” law, enacted in 1994 indicates that criminals with a severe felony and two other convictions must receive a life sentence [to discourage and debilitate offenders] (Jouet 2019). Policies as such significantly impact incarceration rates and disregard rehabilitative measures entirely.

In the Lockyer v. Andrade case, an offender, who also happened to be Hispanic, was sentenced to 50 years for shoplifting $153-worth of videotapes. His previous convictions were theft, burglary, and marijuana transportation. The Supreme Court decided the case was not a violation of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which protects citizens from “cruel and unusual punishment” and preserves their dignity. Around the same time, Justice Anthony Kennedy noted that nations like England, Italy, and Germany are able to retain much lower incarceration rates than the U.S., insinuating that the nation is in grave need of prison-system reform (Jouet 2019). Indeed, the U.S. prison system has surpassed humanitarianism and is headed toward the holding of a purely penal perspective if it has not adapted the view already.

Present data and qualitative information regarding the faultiness of the punitive system and its negative impact on recidivism and incarceration have long been understood. Thus, it is important to get an in-depth look at how the system paves the way for inmates to get reconvicted post-release and how this simple fact, along with racist, lengthy, and unfair prison sentences contribute to mass incarceration.

How does the current prison system in the U.S. impact recidivism rates and mass incarceration? Overall, how effective is the punitive approach in deterring crime and reintegrating released criminals?

Theoretical Analysis and Perspectives

Previous studies have addressed the issues named above with variegated approaches, designs, and methods. Critical race theory is one suitable theory to arch over this study, as it observes the underpinnings of racism that can be found across the legal system historically and today. It was scholastic activists who coined the term in the 1970s to reveal politically discriminatory practice hidden before the eyes of all Americans (Jeffers 2019).

Disparity in incarceration and the justice system may be undoubtedly exemplified by the fact that “…people of color make up 37% of the U.S. population but 67% of the prison population” (Jeffers 2019:115). This disproportion is only an issue in the wider phenomenon of mass incarceration. Furthermore, an examination of deterrence theory and its implications in the U.S. criminal justice system also reveal a flawed approach which is doing less to reduce crime and more to increase recidivism incidence.

Of the fundamental sociological theories, conflict theory would best illustrate the essence of the problem, being the perspective utilizes a critical lens of structural relations. Theorists would agree that the system is destructive to the individual and defeats a person before placing them back into society.

In a 2016 descriptive theoretical essay, Kelli Tomlinson from a Tarrant County corrections department noted deterrence theory to “…[propose] that individuals who commit crime(s) and are caught and punished will be deterred from future criminal activity” (33). It condones the retributive approach in essence. Additionally, general deterrence is a term indicating that the general public witnessing apprehension of others will deter them from offending themselves (Tomlinson 2016).

Although this is a widely believed and trusted perspective in the U.S., studies indicate punishment and incarceration have minimal effect on deterrence. Don Stemen of the Criminology department at Loyola University reported that “…the increased use of incarceration accounted for nearly zero percent of the overall reduction in crime [since 2000]” (2017:1). There is clear evidence to show the current system is lacking in its efforts to reduce crime, but further inspection is necessary in the realms of punitive justice in contrast with rehabilitative justice.

Moreover, deterrability is a separate notion that deserves attention in the field of criminology, as “…deterrence works for some people, but not for others. Some individuals are ‘deterrable,’ while others are not” (Tomlinson 2016:37). With the current system, it is assumed that all individuals learn similarly, so all prisoners will take punishment the same way: they will not re-offend because of the punishment they received. However, all people approach and react to stimuli differently. Hence, deterrence theory “…should not be considered a ‘general’ theory of crime, or a ‘general’ solution for all crime” (Tomlinson 2016:37).

Most empirical evidence indicates that punishment plays less a role in deterrence than do non-legal factors, which could include jobs, friends or peers, marriage and family, ostracism, shame, disapproval, morality, and other external factors as such. These indicators are reported to be much more likely to bring forth conformity in people when compared to sanction threats.

Research also plainly indicates that the present criminal justice system’s inadequacies actually diminish possible deterrence due to the harsh treatment in progress, despite criminals acting rationally upon committing crimes and/or confinement, demonstrating that the punitive approach could be making acting criminals worse. Components of detention facilities, such as referring to them as “maximum security,” their lack of windows in cells, and the limited access to the outside world best cause inmates to feel a low level of sanity, especially since they are treated as if they are insane.

Social learning theory implies that positive reinforcers promote repeat behavior and that offenders are most influenced by their surroundings, making it difficult to perceive the morally proper way but only the way that is observed (Wood 2007). In addition, people are amongst differentiated cultures which promote various actions or viewpoints as the norm.

Oftentimes, offenders are drawn to their behavior to gain respect from those around them, much like an honors student wants to achieve high grade points around their instructors and peers or like a sociological researcher wants to publish new findings amidst colleagues. It is critical to consider the influence criminals draw upon when it comes to how to alleviate their habitual deviance, and the consideration is nonexistent in retribution.

Related is the influence inmates have on one another. People in jails and prisons “…absorb and internalize definitions about costs and benefits associated with crime that they learn from other offenders” (Wood 2007:18). Prisoners learn that their behavior is “good” because everyone around them is on the same page, similar to the common idea that one uses marijuana regularly because of associative learning about it pleasurable to do so, whether the new user personally feels alike or not (still looking for the study supports this). And much like how peers and the environment influence behavior, negative and destructive conditions in prisons overall are only rationally able to promote negative or destructive behavior. The environments of criminals locked up are also minimally researched and needing observance in connection with conditional behavior that ultimately leads to recidivism.

Comparative Analysis: What About Other Countries?

When inspecting approaches and rates in other countries, it is seen that alternative, more mentally considerate approaches deem more successful with deterrence. Turkey’s juvenile criminal justice system emphasizes rehabilitation and freedom of inmates, as they are evaluated upon entry by forensic specialists regarding their crimes and their thought processes (Laird 2021). They have adopted an “open prison” system emphasizing education, work experience, fitness, and community service. There are no fences, and detainees are given allowance to spend time with family. Inmates rarely ever attempt to escape the prisons since conditions are laid back, educational, and often better than conditions at home. Their recidivism rate remains relatively low.

The goal is to release inmates with no remaining threat to society and as productive individuals. As Turkey is only one example, other countries like Germany, Norway, Finland, New Zealand, Netherlands, and more exhibit similar approaches with successful outcomes. The director of a prison in Norway claimed that all their released offenders are effectively back into society, and he questioned whether people want prisoners released angry or rehabilitated, which is an important question to ask.

What Can Juveniles Tell Us?

Looking at younger offenders afresh, since juveniles are potential, future criminals, it is crucial to offer them guidance at first offense to decrease the probability of them becoming adult offenders. Illinois was the first state in the U.S. set up a juvenile justice system in 1899. As it spread, the approach across the country was rehabilitative but shifted within 25 years to retribution. The movement “…marked the most substantial growth in youth imprisonment in the history of American crime policy” (Laird 2021:595).

In about 20 years, there was a 40% increase in the juvenile incarceration rate. Now, the rate is multiple times the rates in most other nations, including South Africa (5x), England (7x), Australia (13x), France (18x), and Japan (over 3,000x).

Consequences of Incarceration

A higher incarceration rate not only keeps a large proportion of the population behind bars and under harsh, disastrous conditions but also costs taxpayers, cities, states, and the country a substantial amount of money, as housing a single inmate costs between $30,000 to $60,000 per year. And research solidifies that there is a very weak relationship between high incarceration and lower crime rates. The system is only a reflection of the whole American approach, which requires reformation replicating what many other more successful countries are engaging in.

Disproportionality and Legal-Targeting

Disproportionate incarceration is another problematic truth across jails and prisons, backed by research. A study gathered data from each state to unveil incarceration by race and found that Blacks are put behind bars five times more than Whites, while Hispanics are two times more (Sakala 2014). Whites make up approximately 60% of the U.S. population, while Blacks make up 13.4% and Hispanics 18.5% (U.S. Census Bureau 2019). Despite these proportions, 39% of the incarcerated population is White, while 40% is Black, and 19% is Hispanic (Sakala 2014). The incarceration rate for Blacks is 2,306 per 100,000, and that for Whites is 450.

QUICK FACTS

- Blacks are incarcerated 5x more than Whites

- Hispanics 2x more (Sakala 2014)

- Whites make up ~60% of the U.S. population

- Blacks make up 13.4%

- Hispanics make up 18.5% (U.S. Census Bureau 2019)

- 39% of the incarcerated population is White

- 40% is Black

- 19% is Hispanic

Blacks are incarcerated at staggering rates when associated with their population in the U.S., indicating there is a racial and targeting issue potentially present within the legal system. Devon Johnson of the University of California, Los Angeles hypothesized that “Punitiveness is associated with racial prejudice” in a 2001 study (39). By large, White participants in a survey indicated high levels of support for the death penalty and harsher courts. Johnson also found that punitive attitudes among Whites positively correlate with income, indicating a generalized perspective across most rich, White folk regarding prosecution.

This points to the wider problem across the legal board and judicial branch with concern to who represents and decides for offenders or defendants and how their perspectives and beliefs could only encompass a single direction. Apart from state or federal delegates, law enforcement who criminals are in direct contact with could also be acting on taught prejudice.

In a separate study, Walter Enders et al. scrutinized racial disparity in incarceration, finding that rates have been high for decades (2019). The 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act exacerbated the issue, as it “…established mandatory minimum sentences for federal drug offenses” (Enders et al. 2019: 367). The act set the same sentence for more crack cocaine and less powder cocaine, and it is no coincidence that crack cocaine is most commonly used by Blacks, while powder cocaine by Whites. Specifically, for possession of five grams of crack cocaine but 500 grams of powder cocaine, the minimum sentence [for both] is five years without parole.

This is a clear racially discriminatory attitude engraved in policy and the minds behind their passing which is targeting Blacks, endorsing bigotry behind law. A more current generalized belief has become that Whites abusing substances have medical issues, but Blacks under the same circumstances are criminals engaging in illegal activity (Jeffers 2019). This is similar to how Whites committing mass shootings at schools are troubled individuals, while others of color, especially those of middle eastern origin, are referred to and treated as terrorists by Americans and the legal system. Such instances of disparate views and treatments birth a cycle of recidivists in communities of people of color, passing a mistrust of the justice system down generations.

On top of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, three-strikes laws and truth-in-sentencing laws, which require offenders to serve at least 85% of their prison sentences, both increased the overall length of sentencing, which has left more and more people in prison, contributing to mass incarceration.

Further, the longer inmates are punished and kept under the substandard conditions of prisons, the less likely they are to reintegrate into society properly. Quoting the Dellums Commission, Janie Jeffers of Howard University emphasized the point, “Incarceration also limits the life options of young men of color upon release, as they struggle to reenter society and the workforce with limited skills and resources” (2019:114).

Prison Conditioning, Reintegration, and Rehabilitation as an Alternative

Frankly, prisons deplete the capacity of individuals, disabling them from becoming productive and contributing members of society. They come out with an inevitably higher likelihood of reoffending due to the destructive conditions they are departing from, their mental health and perceived sanity is lower, they will suffer from heavy stigmas, and their records will obstruct them in job obtainment.

Adjacent to racial disparity in incarceration, again, are destructive prison conditions and the lack of resources for inmates. Nally et al. empirically found that an offender not exposed to correctional education programs are “…approximately 3.7 times more likely to become a recidivist offender after release…” compared with offenders exposed to the programs (Nally et al. 2012:69). Within the group who attended the correctional education programs, the recidivism rate was 29.7%. The latter group had a 67.8% recidivism rate, indicating that access to education and correctional rehab when incarcerated significantly aids in the reduction of recidivism across criminals.

Similar to this study, Metaja Vuk et al. looked at the opinions of people about punishment and rehabilitation via the survey method and found that only one in five participants favored punitive conditions, while more than 60% favored rehabilitative conditions. Although findings from previous decades indicated a preference for punitive approaches, they included a disproportionately high number of White and elderly participants, on top of the studies being during more racist eras.

What Now?

So, which approach will yield the best results? Should the U.S. remain the leader of the world in incarceration and recidivism rates, or should reform be a notion of consideration in the legal sphere?

We could ignore these issues altogether. Yeah… on second thought, might as well put all this aside. It’s not my problem, right? Or yours. There’s nothing we can do anyways. It’s not like this article is going to enlighten congress or something lol. Whatever. I’m going to bed.

Keywords: Recidivism, Prison conditions, Disproportionate, Mass incarceration, Unfair sentencing, Failed reintegration, Injustice, Bigotry, Punition/Retribution, Rehabilitation, Critical race theory, Deterrence theory, Social learning theory

References

Antenangeli, Leonardo, and Matthew R. Durose. 2021. “Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 24

States in 2008: A 10-Year Follow-Up Period (2008–2018).” U.S. Department of Justice.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 256094. 1-28.

(https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/recidivism-prisoners-released-24-states-2008-10-

year-follow-period-2008-2018).

Enders, Walter, Paul Pecorino, and Anne-Charlotte Souto. 2019. “Racial Disparity in U.S.

Imprisonment Across States and Over Time.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 35

(2): 365–92. doi:10.1007/s10940-018-9389-6.

Jeffers, Janie L. 2019. “Justice Is Not Blind: Disproportionate Incarceration Rate of People of

Color.” Social Work in Public Health 34(1): 113–21.

doi:10.1080/19371918.2018.1562404.

Johnson, D. 2001. “Punitive Attitudes on Crime: Economic Insecurity, Racial Prejudice, or

Both?” Sociological Focus[SI2] 34(1): 33–54. doi: https://doi-

org.libproxy.lib.ilstu.edu/10.1080/00380237.2001.10571182

Jouet, Mugambi. 2019. “Mass Incarceration Paradigm Shift?: Convergence in an Age of

Divergence.” Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 109(4):703-768

(https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/mass-incarceration-paradigm-shift-

convergence-age/docview/2328344948/se-2?accountid=11578).

Laird, Robert. 2021. “Regional International Juvenile Incarceration Models as a Blueprint for

Rehabilitative Reform of Juvenile Criminal Justice Systems in the United States.”

Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 111(2):571-603

(https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/regional-international-juvenile-

incarceration/docview/2528247639/se-2?accountid=11578).

Link, Alison. J. and D. J. Williams. 2017. “Leisure functioning and offender rehabilitation: A

correlational exploration into factors affecting successful reentry.” International Journal

of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 61(2): 150–170. doi: https://doi-

org.libproxy.lib.ilstu.edu/10.1177/0306624X15600695

Nally, John, Susan Lockwood, Katie Knutson, and Taiping Ho. 2012. “An Evaluation of the

Effect of Correctional Education Programs on Post-Release Recidivism and

Employment: An Empirical Study in Indiana.” Journal of Correctional Education 63(1):

69–89.

Sakala, Leah. 2014. “Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State

Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity.” Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved October 7,

2021 (https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/rates.html).

Smith, Hayden P. and Robert J. Kaminski. 2011. “Self-Injurious Behaviors in State Prisons.”

Criminal Justice & Behavior 38(1): 26–41. doi: https://doi-

org.libproxy.lib.ilstu.edu/10.1177/0093854810385886

Stemen, Don. 2017. “The Prison Paradox: More Incarceration Will Not Make Us Safer.” New

York: Vera Institute of Justice 1-12.

Tomlinson, Kelli D.. 2016. “An Examination of Deterrence Theory: Where Do We Stand?”

United States Courts 80(3): 33-37

U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. Quick Facts: United States.

(https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI225219#RHI225219)

Vuk, Mateja, Brandon K. Applegate, Heather M. Ouellette, Riane M. Bolin and Aizpurua Eva.

2020. “The Pragmatic Public? The Impact of Practical Concerns on Support for Punitive

and Rehabilitative Prison Policies.” American Journal of Criminal Justice : AJCJ

45(2):273-292 (https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/pragmatic-public-impact-

practical-concerns-on/docview/2376512220/se-2?accountid=11578). Doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12103-019-09507-2.

Wood, P. 2007. “Exploring the Positive Punishment Effect Among Incarcerated Adult

Offenders.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 31(2): 8–22. doi: https://doi-

org.libproxy.lib.ilstu.edu/10.1007/s12103-007-9000-4